Dedicated to creative approaches to patternmaking, Timo Rissanen is a designer, thinker and maker who pioneers zero-waste fashion design. Through his role as Assistant Professor of Fashion Design and Sustainability at Parsons School of Design, Timo is interested in how fashion can be used to enrich our everyday lived experience. In this second interview for Fashion Unlearned Address contributor Emily McGuire speaks with Rissanen about zero waste design processes and why systems thinking is essential to creating a sustainable fashion industry.

Hoodie and Jeans by Timo Rissanen (2008). Image: Mariano Garcia

Emily McGuire: What frustrates you the most about the way the current fashion system operates?

Timo Rissanen: Although there is increasing agreement that things aren’t working, there is still a resistance to taking on sustainability issues at the level that is required. A lot of solutions are on a very surfaced level and focus on single issues. Single issues need dealing with too, but there’s also a systems view that is needed as a framework for all those things. For me, systems thinking is the ability to see the complex ways in which different systems are interconnected. As an example, a simple cotton T-shirt is part of systems of water, nitrogen, agriculture, labour and commerce, to name five of probably countless systems. To understand sustainability is to understand the complex interrelations of different systems.

The industry still doesn’t have the ability to take a systems view because there’s a lot of people who just don’t know how to approach things from a systems perspective, so there’s a level of education required for people in the fashion world. That is where I get frustrated sometimes, the lack of systems thinking and acknowledging the complexity of these problems as well. There is always a simplification of things that tends to happen.

In April H&M staged its Global Recycle Week initiative, which was at the same time as the annual Fashion Revolution event. Lucy Seigle stated that H&M intentionally clashed with the campaign, which the brand claims is a coincidence. Do you think it’s possible for different models for sustainable fashion practice to co-exist if they oppose each other ideologically?

That would be my question, too. The timing was pretty odd. Both models are crucial. The work Fashion Revolution does is crucial. And so is the work H&M is doing regarding the circular economy. They still have a tonne of work to do, but at the same time they’re one of the few brands doing something, at least in the genre of fast fashion. They are leading the way if you compare them to Primark or Zara or Forever21. The timing really sucked. That said, there are definitely opportunities to work together. I’m still waiting for them to respond to my hashtag for #whomademyclothes from a year ago.

I have this organic cotton tuxedo jacket from H&M; actually H&M gave it to my former boss who gave it to me. It still had the tags on it and it retailed for $99. I don’t know how you make an organic cotton tuxedo jacket for that much. I guess the margins would be very low, but I know what it takes to make a jacket, and I have some understanding of what it takes to grow organic cotton. H&M have issues around labour but then again, they’ve made a commitment that by 2018 they’ll pay a living wage to their garment workers. Of course, my first reaction was, if H&M knows they’re not doing that now, why not do it now? I read an interview with the sustainability manager for H&M where she was asked about this, and I read it very generously [laughs]. Living wages can be vastly different across Bangladesh; even in the United States there are differences from state to state. I understand the decision from their perspective, that as a massive company it will take some looking into. It is also exciting because here is a big brand saying, ‘we’re not paying the living wage to our workers right now’. You couldn’t even imagine hearing that kind of admission five years ago. So, things are definitely moving. Thank heavens for people like Orsola!

H&M makes noise about sustainability, so they will be held to a higher level of account by organisations like Fashion Revolution. At the same time we really need to start pushing some of the other big fast fashion brands.

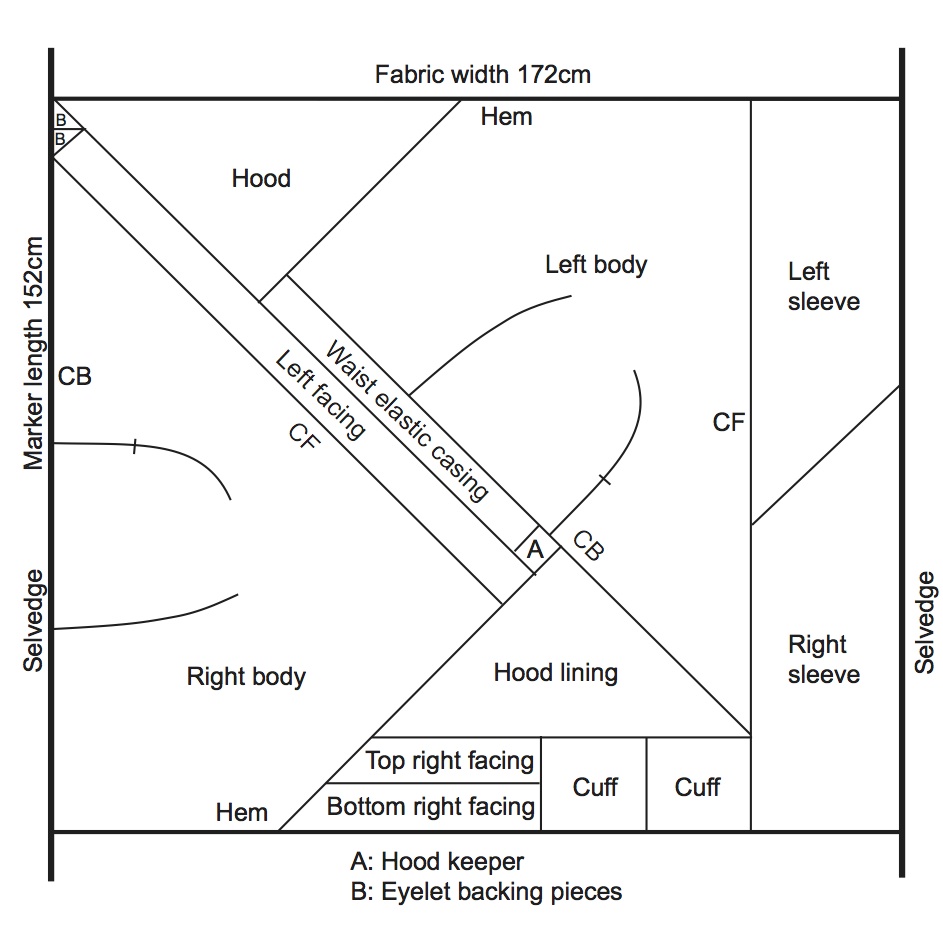

Zero-waste pattern for striped hoodie by Timo Rissanen (2008). Source: Timo Rissanen

In many ways, sustainable fashion has been capitalised on and has become another way to encourage consumption, effectively contributing to the very same issue that sustainable models attempt to reduce. What are your thoughts on this?

It is a key question because often people think of sustainable fashion as some other product category alongside everything else. That is where the “conscious collection” model doesn’t work because brands are saying, “here’s our stuff, and here’s our sustainable stuff”. That needs to be challenged. It’s going to require a shift in mindset because our notion of what constitutes a good quality of life is very much connection to consumption. Projects like Local Wisdom point to ways of being and existing in the world that show you can have a great quality of life that doesn’t rely on buying more.

It seems as though there is more and more organised protests happening in fashion’s manufacturing capitals where workers are desperately demanding fairer working conditions. Although there’s increased momentum toward sustainable fashion practices in other parts of world, notably via Fashion Revolution, it seems like first world consumers are generally lethargic when it comes to actively protesting for brand transparency and sustainability in a targeted and organised manner. Why do you think this is?

A garment worker dying in Bangladesh can be very abstract for people. The impact fades fairly. It is when people see the impact directly on themselves that they start to activate. I think we will see this in the next few years. There’s some research coming out that suggests this. For example, the dyes and other chemicals used in textile processes actually persist in clothing through multiple washings and we also absorb them through our skin. If that indeed is the case, that we are absorbing these chemicals and they are still within existing regulations, I think people will begin to activate against that. People need to be personally invested in order to care about people they don’t know. And most people don’t know that the reason they can buy a $5 T-shirt is because slaves picked the cotton it is made from. Going back to your question, I really do think it takes one-on-one conversation to get people invested in something other than themselves. I think it is slowly changing. Going back to Fashion Revolution, I think the campaign has cleverly tapped into what is a fairly narcissistic moment in our time. Apparently, everyone loves a selfie, and that’s been the brilliant part about it – it can be about you but there’s actually a connection to something deeper. Hopefully we’ll see every day as Fashion Revolution day in the future.

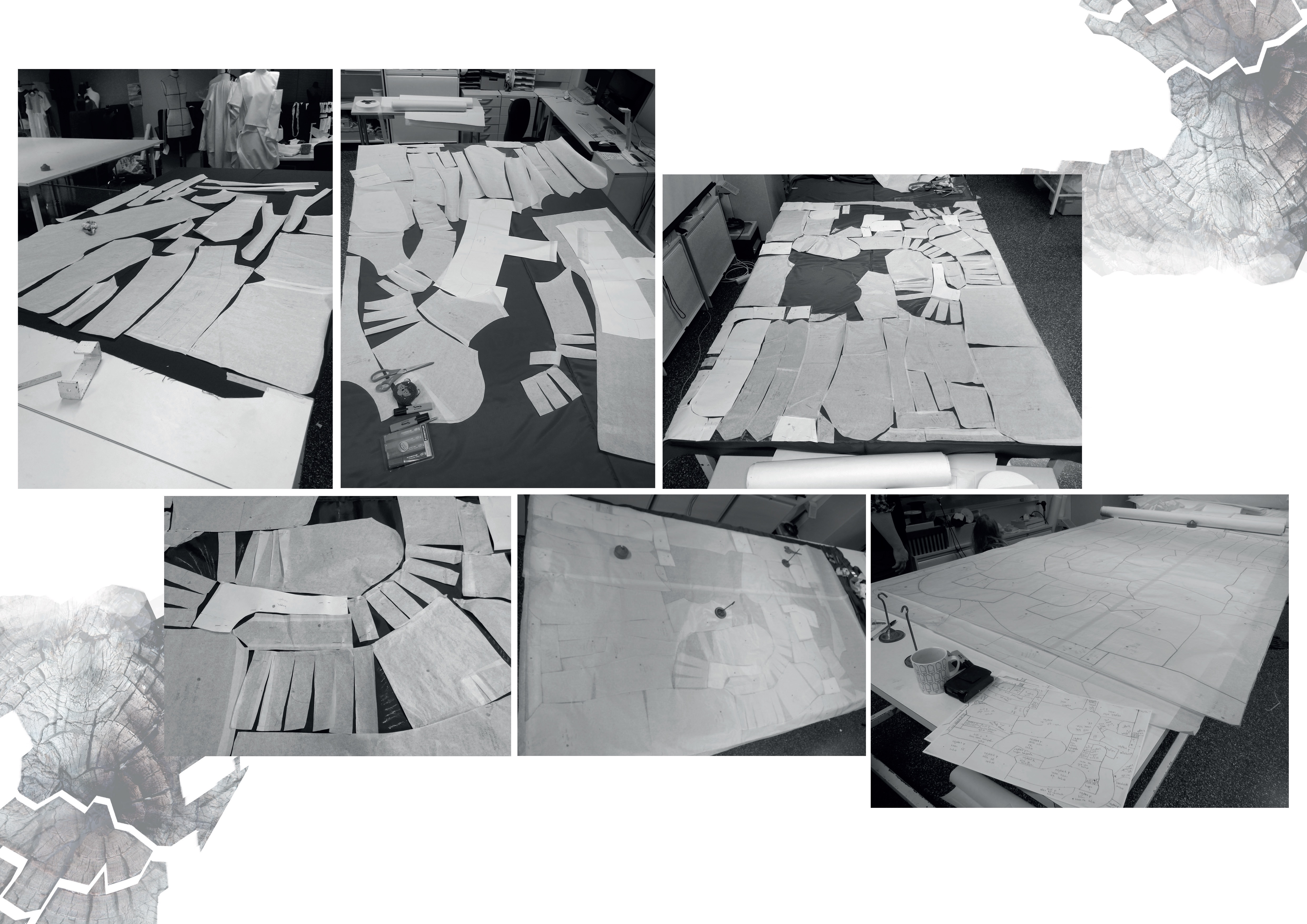

Design process by Jennifer Backlund & Anni Tamminen, Lahti University of Applied Sciences (2014). Source: Timo Rissanen

Zero waste fashion calls on collaborative creative processes and a sense of community among different industry departments, and among users. At the same time, students often learn about fashion design via the idea of the designer as a sole creator, an image that is obviously embedded in the historical development of the modern fashion system. How do you find teaching students to embrace design as a process that centres shared, process-driven practices rather than a focus on autonomy, exclusiveness, and results-driven outcomes?

It is really difficult! When I hear teachers talking to each other and also when I listen to students, the terms “group project” and “group work” are particularly loaded. Last year was the first time I actually said to a student in the elective zero-waste unit, “you might want to consider doing this course as a paired project”. In Zero Waste Fashion Design, which I co-authored with Holly McQuillan, there are a number of photos from the Lahti University of Applied Sciences in Finland that’s been teaching zero-waste since 2011. They always do it as a paired project because they think two brains trying to solve this kind of complex issues is better than one. They have been very successful with it – it has been running now for five years and the work coming out of that course, to me, is of very high quality. I’ve not had any students work on the zero-waste project at Parsons in pairs. I think it would have to be imposed on them.

In a slightly different context, last autumn we did a course on sustainability focused on designing for use practices, primarily laundering, and it was in partnership with a detergent brand. They gave us a very generous project to develop a collection that had to be entirely machine washable. We had the opportunity to put a lot of things through a washing machine that you wouldn’t normally, so the final collection had fabrics that you’d never imagine being washable like silk gazar, silk organza, different wool suitings and so on.

We had 15 students in the class and we instructed them to work and function as a team. For feasibility, we divided the class into smaller groups of three or four students. During the semester, we had to come to a collective agreement on what the fabrications would be and that happened fairly late in the game. Even then, in the final week when the students presented the collection to the external partner, fabrics were used that the whole team didn’t agree to. Their unwillingness to compromise was interesting. I get it, in every other class it’s about you and your point-of-view, but I don’t think we teach enough about collaborative work to fashion students at university. Some students showed leadership in their groups because they were able to compromise on their own ideas for the benefit of the team and the collection. As far as fashion education goes, collaborative work has become more present in conversations around curriculum and pedagogy.

I feel like it involves a process of unlearning to explore zero-waste because it challenges you to question the traditional design methods you’ve been exposed to over and over again.

I think unlearning is a good word. If you look at the big picture of sustainability there is a lot unlearning we need to do as a fashion industry as well. I think we should start with the question, ‘why are we doing this?’ I’m on an advisory board with the CFDA and they have a partnership with Lexus. They use to offer a cash prize for brands that were doing something around sustainability. Now, it is an 18-month long mentorship program for 10 brands and I’m involved with mentoring those brands. One of the main things that have come up, is the amount of plastic packaging at the design level, which brands are expected to put garments in when they are shipped to retailers. There is an expectation that each garment arrives in an individual plastic bag. We really need to start challenging the idea of single-use plastic within the industry. Even recycling is expensive, and it is very resource intensive.

Zero-waste pyjama set by Timo Rissanen (2011). Source: Timo Rissanen

In what ways have you seen students become really empowered in their creative practice through their engagement with zero waste design processes?

The main thing that tends to come out of it for students is a heightened appreciation for fabrics from working with zero-waste. You start to think of fabric as a much more precious material. The way I see students approach fabric, they relate to it as if it is as valuable as toilet paper. Even those students who don’t continue using zero-waste tend to become more creative in the way they use pattern making in the design process. It’s really difficult to teach someone to become a great zero-waste designer in one semester. The other thing that delights me is when students take on zero-waste independently without learning it academically. Those students are always an inspiration to me.

What would you like to see universities do in fashion education to equip young fashion practitioners with the skills and the mindset to agitate change to the fashion system?

Systems thinking is really important. Students need to able to perceive the whole system, even when they’re focusing on one specific part of it. We also need to start moving away from glorifying design as the only pathway into fashion. Fashion has had this weird moment for the past 15 years. It’s easy to blame the TV show Project Runway and I often do. It is not the only cause, but it has played a part in creating this illusion of the star designer. It is about the individual over everything else. We need different kinds of skills. We need really good pattern cutters, really good embroiderers, and really good textile designers. We need people who know everything about knitting. As institutions, we need to support different individuals becoming experts in different things, rather than gearing people toward becoming the next McQueen. Those people will emerge naturally out of the numbers as they always have. At Parsons where we have 300 fashion bachelors graduating every year. We have recognised that it has been a long process to shift the curriculum to be more open and geared toward student interests.

We are about to launch the fourth year of this new curriculum. So, next year students are not required to do a collection for their final work; there are a variety of options for them. As an example of this, a year ago we had one student graduate who, for the two years leading up to her collection, worked with people who had different physical disabilities. Her final work was fashion design for people in wheelchairs and included extensive garment components rather than six complete looks. She ended up winning our Designer of the Year award. My guess is 90 per cent of students will probably still do a collection, but at least now there’s room for the 10 per cent to explore other issues.

Timo Rissanen recently co-authored Zero Waste Fashion Design (2016) with Holly McQuillan. This resource provides practical guidance on how to design clothing for zero-waste alongside interviews with designers and makers working in this area of sustainability.