For too long, the so called ‘high-end’ fashion designers have maintained that fashion is a product of a singular creative vision where the labour of making is often hidden. In an attempt to shift this perception, Performative Processes aims to highlight the collaborative nature of fashion by making the production visible in open workshops and by creating a space where dialogue can emerge around sharing of skills, knowledge and creativity. As part of the on-going ‘Fashion from the Shadows’ series, Aïcha Abbadi collected some of the most exciting examples at the forefront of this participatory approach to fashion.

Onesie World by Adele Varcoe (2018)

“Choices are made because they yield the biggest profit margins, not because they are more beautiful or because they make us happier. How you dress is about how you position yourself in the world. How do we take fashion back into our own hands and make it a catalyst for social change?”

Pascale Gatzen (2018)

ETHOS

Performative Processes aim to celebrate the collaborative making of fashion in a playful way. Open to those who are interested in participating, this approach seeks to transform the exclusive or hidden methods behind fashion into public events. Transformative and educational, Performative Processes promote positive experiences as well as productive critical thinking devoid of nihilist inertia. Instead of isolating and separating those involved in the process, participants in this approach encourage communal experiences, public discussion and intimate dialogues. Perspectives on fashion are shifted from a form of individualistic self-expression and invisible labour towards a collective and highly visible social practice that occurs as much through processes of making as performing and language.

Performative Processes act as an antidote to the mythology of fashion idols, exclusivity and hierarchical thinking. Designers, producers and wearers switch from one role to another and become equally valued collaborators. In the process, their simultaneous embodiment of multiple roles highlight the role-playing side of fashion beyond ‘dressing the part’. Performative Processes go further and present a new perspective on the roles performed by industry members within the fashion system and prefigure alternative dynamics between those involved in the processes of making and imagining. Beyond the confines of highly specific job titles within the fashion industry, participants opt for liberating formats whilst reassessing what it means to work in fashion. The processes result in projects that highlight social interdependency and put a focus on a sense of belonging while examining preconceived notions and prejudices as well as celebrating the unplanned within moments of interaction.

Performative Processes are both planned and open-ended, imagining a mode of engaged and playful fashion production. They are often considered artistic practices and are thus quickly positioned outside of the world of fashion. However, as fashion research beyond historical studies of dress has become more established, it has given rise to more creators who are not merely commenting on fashion but rather through fashion. They open up new possibilities for the discipline and thus operate at the forefront of fashion rather than on its sidelines.

Deeply informed by fashion theory and yet maintaining an openness as well as a state of creative flow, Performative Processes focus on human relationships, self-image and the perceptions we have of others. Where established style codes and ‘mass individualism’ have resulted in rigid structures that leave no space for creativity and collaboration, Performative Processes act as interventions that reconfigure social interactions and shake up fixed self-perceptions to present new ways of working and being together. The process highlights what fashion can do when used as a tool for defining ourselves together through dialogue rather than defining oneself against another.

KEY TACTICS

Performances, Collaborative Making, Interventions, Festivals, Public Discussions, Exhibitions, Co-Authorship, Interaction Documentation

Nexus Architecture by Lucy Orta (1998)

CONTEXT

Critiques of fashion and adornment as a social practice have been expressed consistently since its inception, yet extensive critiques directed towards the complex processes behind fashion appeared only after the late 1970s. They accompanied the steady expansion of mass-produced fashion with its faster cycles as well as the rise and multiplication of mass media. Similar thoughts were expressed by cultural critics, disillusioned newcomers and industry veterans alike. In tandem with fashion’s processes of production and communication, every decade sees its own surge of public criticism against the system of fashion, focusing specifically on its elitism and processes of social stratification. Beyond demanding ethical practices, critical practitioners have also formed appeals for more creativity, collaboration and alternative processes. Yet these widely discussed concerns often lead to resignation. This results in superficial changes or a nihilist questioning of purpose, and drives many former fashion practitioners to move on to other fields. Rejection of the status quo is frequent and drop-outs disappear from fashion’s discourse. This leads to many critiques and processes repeating themselves without moving forward.

Artists, writers and activists have continuously aimed to put up a mirror to the inequalities created by consumer society and have actively participated in or influenced outlets dedicated to the capitalist critique of fashion. Canadian magazine Adbusters has repeatedly created visual critiques of mass fashion brands by subverting their advertising and calling attention to the discrepancy of earnings of those involved in the different layers of fashion production. Their oppositional stance aims to inform the public and dismantle fabricated constructs of fashion communication in real time. This approach provides an important base for discourses as well as debates and generates provocative artworks. Yet, within the context of fashion, it is more reactive than creative and paints a bleak picture for the future of fashion. From Nicholas Coleridge’s The Fashion Conspiracy (1989), to Teri Agins The End of Fashion (1999) and Dana Thomas’ Deluxe: How Luxury Lost its Lustre (2008) as well as multiple other publications covering the mechanisms and deficiencies of the fashion system, the topic was clearly not yet exhausted when Li Edelkoort and Trend Union published the Anti_Fashion Manifesto in 2015 and provoked a wave of industry reactions. During a moment of general uncertainty, the Manifest was cleverly timed and sold as a limited edition consisting of a few but high-priced pages filled with statements already expressed elsewhere. Ironically, it perfectly mastered the mechanisms of fashion that were supposedly being criticized or perhaps it sought to embody its vision of a couture fashion future via its distribution. However, the Manifest has since evolved into the Anti_Fashion Project which progressed beyond critique in order to propose exchange and collaborations to put the ideas of the paper into practice. Claims of a definitive end of the fashion system have repeatedly been voiced and yet it has successfully continued to exist while perpetually using the same strategies and repeatedly telling the same stories.

The cycle of continuous branding, marketing, appropriation of subcultures and DIY culture with subsequent critique and the appearance of alternative outlets seems inevitable. These repetitive processes and the steady hunt for the ‘new’ has often been the subject of satire and theatrical parodies of fashion, with movies such as Funny Face (1957), Who are you, Polly Maggoo? (1966) or even Clueless (1995). Amplifying stereotypes in the public perception, they are also reinforcing roles within the industry where they are not only produced by, but also subsequently referenced by the primary audience of these works, the fashion practitioners themselves. And yet, with each re-enactment of the fashion cycle, a number of practitioners look for ways beyond this self-sustaining system and imagine different ways of being in fashion. Artists and converted fashion designers, determined not to perpetuate the processes they disagree with while still being productively involved in the discipline, have moved on to imagine more positive and socially inclusive ways of making fashion. They are characterised by their optimistic outlook and radically open approaches, providing a counterbalance to the doubts and strategising of the jaded and those overwhelmed by their goal of changing the system. Their approach succeeds at overcoming typical insider/outsider structures by reinstating the value of community and co-creation in fashion instead of categories that separate designer from producer, consumer from critic.

Anti_Fashion Manifesto by Lidewij Edelkoort/TREND UNION (2015)

Previous incarnations of Performative Processes include Lucy Orta’s Nexus Architecture works that have been performed since the early 1990s and seek to highlight the interdependency of human relationships through simple but strong visual concepts and collective experiences. Using one-piece suits connected to each other at the navel, wearers are connected in a line or a grid, realising how each individual action affects the whole. A strong reminder for a highly interdependent and yet often ego-driven industry, Orta’s work is representative of a more human-, rather than product-centered view on fashion.

Navigating the ambivalent position of a working designer exhibiting in a museum and the often criticised marriage between culture and commerce, Yohji Yamamoto’s Dream Shop exhibition at Antwerps ModeMuseum (2007) constructs and dismantles the ‘dream’. With visitors encouraged to interact with the exhibited clothes, Dream Shop was participatory and playful, yet also functions as a critical commentary on fashion as both artistic practice and consumer product. More than just a shop or showroom within the museum, it highlights the artificiality of spaces and questions our expectations as well as social norms attached to cultural and commercial environments. It also magnifies visitors performing the clothes rather than looking at them or wearing them unconsciously. The exhibition seeks to raise awareness of buying into a dream as a performative process.

With some perspective, these isolated works can now be recognised as the precursors of a shift towards a new expression of ‘togetherness’ and exchange in the process of making and ‘acting’ fashion. This development has been promoted and tested continuously by designer and educator Pascale Gatzen. Seeking to create an alternative to her own isolating experience as a competitive fashion designer for new graduates, she has developed curricula at Parsons School of Design in New York as well as ArtEZ in Arnhem that apply her ideas of ‘radical compassion’ and promoting ‘human values’ in practice. As more students are interested in different social interactions through fashion and independent practitioners are already expressing these concepts in public, new formats and modes of performance beyond the spectacle are paving the way for a more emotionally and socially engaged fashion practice.

CASE STUDIES

Australian researcher and practitioner Adele Varcoe’s work is characterised by performative processes that highlight fashion codes and norms by subverting them. Her claymation videos capture common industry perspectives on fashion but simultaneously disarm perceived authority through imagery that defies fashion’s prevalent visual language. Here, Varcoe is at the same time the puppeteer of well-known fashion figures and a figure among them, directing, performing and commenting at the same time. She also documents the different reactions towards a performance consisting of wearing one-piece suits every day, highlighting people’s preconceived ideas about clothes and context. Through rendering them in a different medium with clay figurines, they are perceived as absurd, surreal situations and prompt the question what radically inclusive fashion would mean.

The aim of Varcoe’s practice is most clearly experienced through her collaborative ‘onesie’ performances. She invites participants to perform the collective production of one-piece suits to the sound of upbeat music, remixed with sewing machine sounds and occasional singing. Throughout the performance, machinists and bystanders alike get dressed in the clothes that have been assembled, filling the space with onesie-clad, dancing people of all shapes and ages. Together, they create a communal experience designed to transmit a sense of ‘oneness’ that is radically different from the usually exclusive nature of ‘belonging’ through fashion.

Having emerged from a disparate group of creative practitioners in the US, IMMEDIATE Fashion School is an ever-changing collective appearing in different cities. Initiated by Tina Sparkles, whose research and practice revolves around social experiences, the project seeks to ‘playfully challenge dominant fashion through study, art and performance’ and carving out spaces for fashion study outside of institutions. Envisioned as an alternative to commercial and industry fashion spaces that links academic discussions to everyday life, IMMEDIATE Fashion School seeks to create fashion dialogue beyond the consumer product and to focus on human interactions. Aimed at erasing the dichotomy of fashion specialists and consumers, (temporary) members of the collective learn from each other and collectively research and reflect on fashion. Through critical readings of fashion theory and discussion groups, the project generates critical dialogues and encourages conversations made up of diverse perspectives and backgrounds. In addition to talks and interventions by the collective, guest speakers are invited for external input. Beyond discourse, IMMEDIATE Fashion School is also a laboratory for practical skill-sharing and collective making that culminates in exhibitions at the end of each season. Shaped by their multidisciplinary backgrounds, participants imagine fashion practices beyond the commercial product and document their findings through collaborative zine-making sessions.

Manora Auersperg’s ‘Abendmahl’ (2011) is a performance where the centrepiece is a wearable tablecloth for multiple participants. Throughout the dinner and conversations about creative practice and culture, the fabric is stained, tracing the interactions between the diners. After the dinner, Auersperg embroiders the stains, fixing the performative process in time and highlighting the interplay of structures and accidents. She is the author of the performance and the artisan embroiderer, but the motifs are co-authored by the participants who make the performance possible. The resulting piece is a memento, a souvenir of an interaction that could be staged but not authored, with the public act of embroidering extending the experience and associated conversations in time, ending with a moment of quiet reminiscence and reflection.

Kids in Fashion was a performance event at the Melbourne Fringe Festival that re-imagined the creative process of fashion. Instead of an experienced creative director or designer guiding what the resulting clothes would look like, children were invited to draw and communicate their designs. Those were then executed by local adult practitioners (RMIT Fashion students), at once reversing power relations commonly at play in the industry and benefitting from the synergy of unbridled creativity of the designers and the expertise of the makers. Such public design experiments demystify the processes behind fashion and put an emphasis on the team nurturing each other’s talents. Instead of reproducing the idea of an isolated genius designer with invisible makers, Kids in Fashion created a low-treshold collaborative environment to experiment with fashion. In addition to playfully engaging the public, such formats could also generate further interest in how clothes are actually made and by whom. This was also explored during the presentation of resulting pieces, where involved children asked members of the audience about the clothes they were wearing and thus incorporating them in the show. As reported by Carissa Lee, the event raised consciousness of fashion as a communicative medium among participants. Designers, models, makers, the audience as well as the DJ all became part of the show for a celebratory presentation beyond fixed roles.

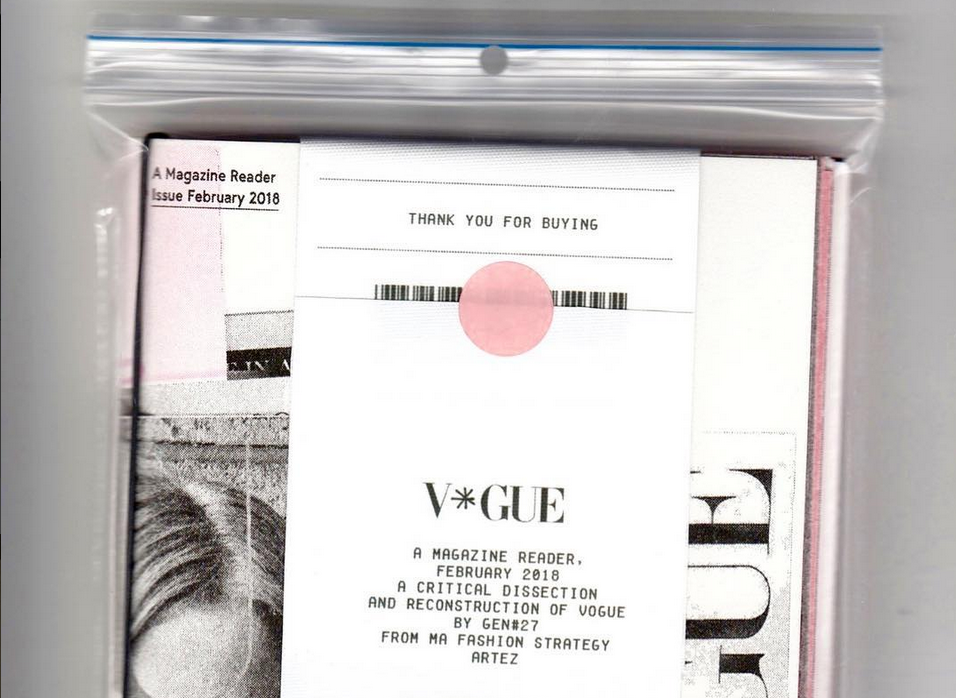

Initiated by designer-researchers Hanka van der Voet and Femke de Vries with ArtEZ’ MA Fashion Strategy course, V*GUE is a magazine reader that examines, dissects and reconfigures a specific issue of VOGUE. Through a collaborative process, V*GUE examines the language of fashion, the role of the reader and consumer of the magazine itself, but also potentially its featured clothes. Through a critical engagement with the magazine, its structure and contents, the format provides a discussion space and re-imagines the relationships between brands, media and the public. The slow and active reading reveals mechanisms of seduction and repetition, the gaps between intended and actual audience as well as the aspirations a reader may have and why. Dissecting and reconstructing gives the reader agency and opens up a space for discussion about readers’ expectations of magazines and the consumer choices that are made. It envisions an exchange between magazine readers as a group of educated cultural critics rather than a consumers’ union. The format is a way of learning about fashion that appears below the surface and raising awareness of the true ‘dress codes’ and seductive power of language.

Fashion from the Shadows

Gathering common motivations that unite a broad range of practitioners, ‘Fashion from the Shadows’ -series aims to map alternative approaches to thinking, creating, presenting and discussing fashion. It provides an overview of recent developments in the discipline in order to integrate them into a new and more inclusive fashion system that encourages discussion. Instead of being suppressed, these alternatives broaden fashion’s spectrum of activities and help to provide a more complete understanding of the spirit of the time which fashion has always sought to reflect.