This tale – as many within this journal – continues the quest to locate and identify constructive, critical and credible fashion criticism. Critical discussion of fashion in popular culture could be understood in two very different ways. One interpretation could be that of a discussion, which finds fault with fashion, the other as a discussion characterised by careful analysis of fashion. By employing both these two interpretations to examine discourses or discussions of fashion within areas of popular culture, it may be possible to find articulate, balanced fashion criticism in unexpected places – perhaps in a place far far away and a time long long ago?

One does not need to examine media in any great depth to uncover evidence of discussions that find fault with fashion. The regular inclusion of articles such as “worst dressed” celebrities on the red carpet and “The 10 Worst Ideas from Fashion Week” in a range of publications from ‘celebrity – gossip’ rags at the supermarket checkout through to ‘Time’ magazine, all contributing to long held notions that fashion is connected with vanity, ostentation and only of interest to the superficial. Historical discussions of fashion and dress put forward by such notable figures as Plato, Kant and Rousseau may have formed the basis for this view of fashion; their philosophical perspectives dismissing fashion by viewing it as a distraction or as a corrupting influence and connecting it with vanity or fraudulent behaviour.[ref]Gonzalez Ana, “On Fashion and Fashion Discourses”, Cultural Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 1, 1, (2010): 65-84.[/ref]

Such criticisms of fashion create uncertainty for those of us who understand fashion to be more valuable in society. If one acknowledges that aesthetic goods, fashion and appearance play an important role in social interaction and identity construction[ref]Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Bantam Doublebay Dell, 1959. and Entwistle, Joanne. The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000[/ref], then the contrasting messages circulating on fashion in the media create a dilemma – my appearance is important – I communicate through it and I am judged on it, however if I am seen to be excessively concerned with my appearance I am judged as vain, superficial and materialistic.

Surely, the reality of fashion is more nuanced than this, affected by a range of pressures and personal motivations – balanced criticism of fashion should reflect this. So, my intention here is not to seek out polite discussions of fashion that describe only the positive aspects of ‘Planet Fashion’ (there are plenty of examples of these circulating in the fashion media), but rather to identify more subtle, credible and thoughtfully constructed criticisms that offers some light and shade.

A review of folk law and children’s stories can provide an unexpected source of thoughtful discourse on fashion and dress. Many of these (predominantly 19th century) tales highlight the faults and flaws of fashion, often focusing on fashion’s role in deception for example, however they also acknowledge its ability to transform. These ideas are communicated in a more artful manner, assisting in the interpretation of value and meaning of fashion and aesthetic objects, rather than the contemporary often one-sided portrayal in certain areas of popular media today.

Brothers Grimm (2003) gave us the story of Little Red Riding Hood in 1812. Along with the main character being defined by her choice of clothing, dress is at the heart of this story’s most dramatic moment, where the wicked wolf has convincingly disguised itself as the grandmother; however the evil plan is thwarted as a sartorially astute Red Riding Hood sees through the costume. The Brothers Grimm utilise the transformatory power of fashion again in Cinderella, in a less sinister context; fashion enables and transforms Cinderella’s life. By wearing the right outfit she gains admittance and acceptance in certain social circles, this changes her circumstances and prospects considerably.[ref]Grimm, Jacob & Grimm, Wilhelm. The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (3rd edition). New York: Bantam, 2003.[/ref]

Hans Christian Anderson (1983) writing in 1836 provided plenty of stories that contain fashion and clothing references, but there are two where fashion plays a particularly prominent role in strong moral messages – The Emperor’s New Clothes and The Red Shoes.[ref]Andersen, Hans Christian & Haviland, Virginia. Hans Christian Andersen: The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories. New York: Anchor, 1983[/ref]

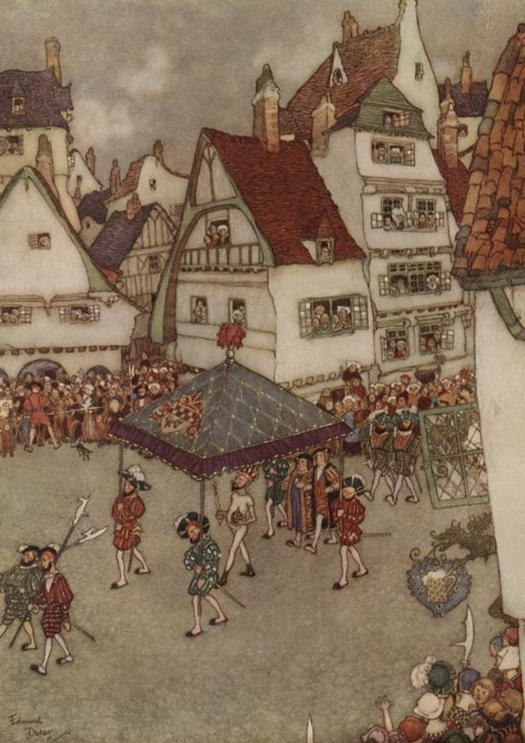

As I am sure we are all familiar, The Emperor’s New Clothes is a cautionary tale of how an excessive interest in one’s appearance may reveal you to be vain, stupid and arrogant. Despite his portrayal here as a buffoon, the Emperor does exhibit some very contemporary traits that we can recognise: anxiety about presentation of self (and how others will judge him), his desire to be perceived as a style setter or tastemaker by his people and acts of impression management as he (and his courtiers) play along with the farce.

Rather than reading the Red Shoes as just another tale of a young woman with a shoe fixation, the Red Shoes can be read as a ‘coming of age’ tale, where the red shoes come to represent a particular time in Karen’s (the central character) life – a phase she grows increasingly ashamed of during the story. We learn through the narrative that this period was clearly a difficult time (adopted by a strict, elderly, sick benefactor). During that problematic time, fabulous red shoes and dancing were a form of escapism – possibly today’s equivalent of some ‘retail therapy’ and ‘a night out on the town’.

These stories use fashion to help construct a narrative and characters with depth, embedding and connecting fashion with eternal social concerns – presentation of self, social interaction, finding love, happiness and riches. The writers craft compelling characters that we can recognise and relate to. Through the power of the storyline, we the reader, get a sense of what it is like to be in the ‘shoes’ of these individuals, whilst gaining an understanding of their motivations to use and abuse fashion – sometimes with good intent, sometimes with evil intent. These criticisms of fashion framed in engaging narratives appear more balanced, more authentic and easier to relate to despite having been written almost 200 years ago.

Of course, these stories were not intended as a vehicle to assign meaning to fashion and dress, most contain a clear moral message. Folk laws and children’s’ stories have traditionally played a role in depicting and explaining societal conditions and communicating cultural norms. The moral message of these stories has been creatively disguised. It is interesting to note the number of tales that make use of fashion, clothing or appearance of characters (Rumpelstiltskin, Rapunzel, Straw Peter, Beauty and the Beast, Thumbelina, The Little Mermaid….), even in passing, as a way of creating an understanding of their traits and social context for the message. Just a little back-story can enhance, personalise and offer greater understanding in critical discussions of fashion; a supporting story line or contextualisation underpinning fashion criticism does much to limit the use of fashion stereotypes and negative assumptions about the field of fashion and those involved with it. The inclusion of descriptions of fashion (and appearance) in these tales of social commentary, highlight the relevance and function of fashion in society and bring human interest to the criticism of fashion.

Since these stories were first conceived, the fabric choice and design details of The Emperor’s New Clothes and the shape and style of the Red Shoes will surely have moved on, along with the moral and social context; however they have an enduring quality that makes their approach to criticism of fashion somehow more meaningful. It is the contextualisation, depth and insight provided into the driving forces included in these tales that enhances the quality of criticism. In their discussion of the subject these authors have captured a range of possibilities of fashion – sometimes magical, sometimes dark – and usually with a happy ending.

Rachel Matthews

A graduate of Central St Martins and Winchester Schools of Art in the UK, Rachel’s career has been a combination of senior posts in fashion education, the fashion industry and international consultancy projects. Her academic posts have included roles at the University of the Arts London and Middlesex University. Rachel is currently head of Melbourne School of Fashion, Australia. She is undertaking a PhD at Monash University, where her research interests focus on the activities of contemporary fashion tastemakers.