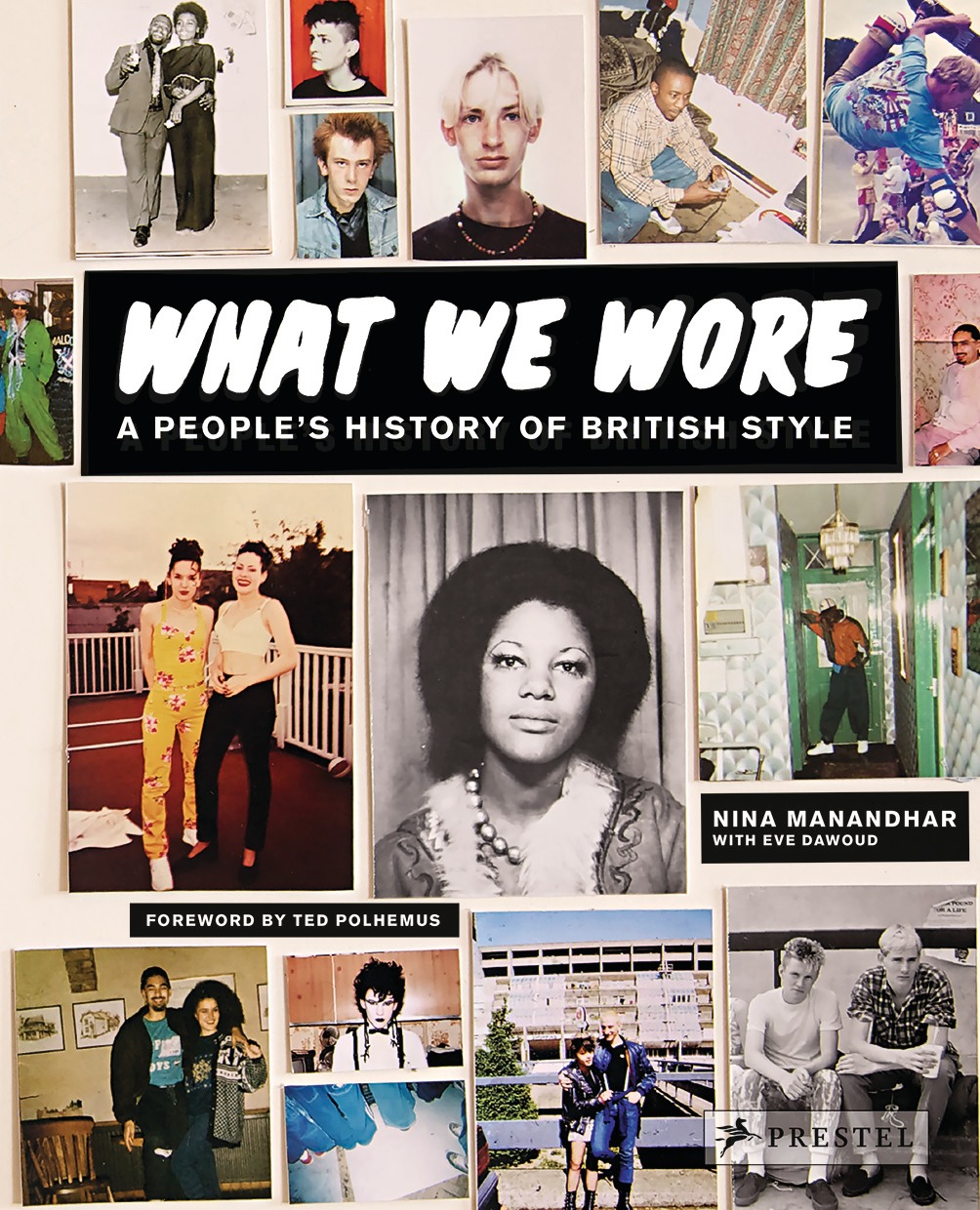

Nina Manandhar is a photographer, artist and modern day pop-ethnographer. Inspired by both the vibrancy of youth and the dynamism of city life, Nina’s work explores how style and culture act as tools for identification and belonging in global youth culture. As the author of What We Wore – A People’s History of British Style, Nina has created a visual timeline of British fashion since the 1950’s which gives reader’s an insight into youth tribes and subcultures whilst recording and explaining UK fashion trends from the past sixty years. Address contributor Grace Wood interviewed the author.

What We Wore initially launched as a website, firstly as part of ISYS Archive and then as a stand-alone site – did you always have the end vision of documenting your findings in a book?

From the outset, I thought the concept would make a great book. I had previously done lots of self-publishing based projects and love the printed medium. I initially approached Prestel about publishing What We Wore as a book with the help of Eve Dawoud, who was heavily involved in the research of the project. It’s great that the book has a mainstream publisher and has therefore been able to get distribution in places like Urban Outfitters and Amazon, as well as independent shops like Claire De Rouen and Donlon.

The book is full of images taken from the personal photo albums of the British public; do you therefore believe the general public capture a better representation of British fashion history and youth style than professional documentation?

Not better, but different. Personal photographs have the ability to tell stories from a different perspective, to use style as an entry point into talking about people’s real lives and histories. They create an insiders look at things, and despite the quality of the photos not always being great, there is energy in them, which is often different to those, which come from the outside in.

source: What We Wore

In addition to the images captured by the general public, What We Wore also features images submitted by creatives within the public eye, such as Tracey Emin – how did these collaborations come about?

I wanted to include people who were known figures in arts, music and culture who represent movements or moments in time, but give them the same treatment as everyday, lesser known people, to whom music and style is equally as important to. I think from a reader’s point of view, it’s great to see your heroes as teens themselves. Many of these people were contacted directly by the What We Wore team and myself.

The personal stories alongside the photographs help to bring the clothing alive, was it just as important for you to incorporate words within the book as well as images?

Although the edit of the book prioritises images, for me the inclusion of text was extremely important too. Words played a vital role in bringing out people’s stories, the small details and nuances of lives lived. Having this access is like being able to step inside someone else’s world, like going back in time and stepping into a strangers living room – my dream time machine. One of my favourite things in the process of creating the book was writing the sub-headers for the images. It’s like bad youth poetry with way too much alliteration, but it was fun for me.

source: What We Wore

You particularly focus on British youth style and mention how in youth, the body acts as a shrine to our obsessions and cultures. Why do you think this form of sartorial expression is often lost by the time we reach adulthood?

To get really basic, the youth obsession is partly about sex and adorning the body. It’s about attracting a mate, and mates. When we are young, we socialise a lot more in public and the body is the most immediate tool for communicating who we are, and for attracting the people we want to attract. When we are more settled in later adulthood, I guess we decorate our homes rather than our bodies and they then become the centre points of our world. It’s different now as people’s relationship patterns change and age is not such an issue – there are plenty of elderly Sartorialists. I don’t think I’ll ever give up on being interested in style. For me, style is a great form of expression and personal creativity and always has been.

In your introduction of the book, you mention how we now live in a world which is obsessed with documentation, an example being the current selfie and hashtag craze. Do you believe this will translate into a positive or negative when it comes to recalling British fashion in the future?

It’s a mixture of both positives and negatives. I think one of the key things about everything now being so instantly visible is there is less time for things to naturally evolve of their own accord. Fashion innovation is also quickly taken out of the hands of its originators and then sold back to them. Yet, on the other hand, I think new technology offers people more of a stake in creating their own ideas and building communities. We are drowning in images and if the internet were to be deleted then these histories would just vanish. Who would step in to retell these stories? I guess that’s why books are so important and why there has been a resurgence of interest in the medium.

What’s next for What We Wore?

There will hopefully be a second edition! I’m also planning to do an exhibition, and possibly expand the concept to other cities and countries. I’m keen to continue exploring the concept of youth representation in my work, and its forever changing landscape.

source: What We Wore

WhatWe Wore – A People’s History of British Style by Nina Manandhar is out now, published by Prestel.

The What We Wore People’s Archive is still open for submission. Email submit@what-we-wore.com